Despite white-Christian support for Donald Trump's wall, authentic Christian tradition remains an inescapably central resource for progressives. Authentic Christian tradition can help progressives to stop America's slide toward a Christianist fascism under Donald Trump—or, for that matter, under Michael Pence or Ted Cruz or Paul Ryan. Progressives have at our disposal thousands of years of eloquent writing by smart people whose values align with ours. It's crazy to turn our backs on that heritage because we are appalled by the fundamentalist corruption of Christianity.

Pragmatically speaking, our political success may in fact depend upon our willingness to use these resources to reassert the moral foundation of American democratic norms. Shrill denunciations won't make a difference: that's preaching to one another. And most of us are weary of these empty rants. We need to persuade Trump's voters, especially those who are or who have become ambivalent about their choice. Authentic Christian tradition offers both sharp arguments and soaring language that progressives can use—if, of course, we are not allergic to anything that hints of "religion."

And that's not all we need. We need to recognize the specific religious anxieties that underlie the cultural and economic anxieties of Trump's base. As Arlie Hochschild has documented, they feel like "strangers in their own land." As I want to explain, feeling like "strangers"—feeling like outcasts and "losers"—is hard-wired into evangelical fears of damnation.

It's an odd story. But progressives need to know it, because Trump consoles this anxiety when he promises his supporters that they will win until they are tired of winning. To erode Trump's support within his base, progressives and Democratic candidates need to understand why his message worked—and thus how to craft an equally successful message of our own. I want to offer a short, sharp backstory–briefing to help any of us to craft such a message, even in ordinary personal conversations with friends or family who support Trump.

Let's begin with the Western moral foundation for human rights, including the rights of refugees on our borders and immigrants who are already living and working in this country. Assuming you read at college-level speeds, that will take two minutes. An analysis of white-evangelical anxieties will take three minutes or so. I conclude with two minutes of practical facts and examples.

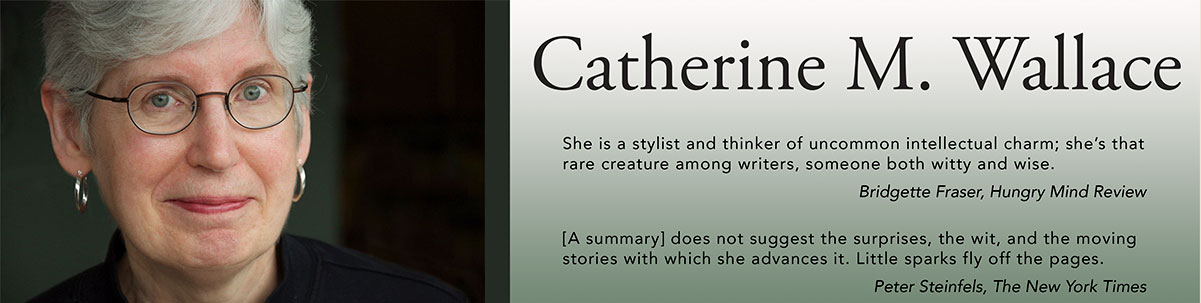

Given how much is at stake, I hope that's not too much time to ask. After 9/11, I spent fifteen years in close, multi-disciplinary, scholarly study of what has gone wrong with Christianity in America and how, systemically speaking, such pernicious attitudes over time insinuated themselves into American culture and politics. I wrote seven books about what I discovered, the last of which was published the day Trump was elected. I had feared for years that the election of someone like him was nearly inevitable.

It is not inevitable that we will defeat him. But it certainly is possible. To win, we need to recognize and to navigate the powerful cultural currents that brought us to this crisis.

That's what I want to explain. I will be as brief as humanly possible. I will provide links to some of my most important sources. For more detail, see my books Confronting Religious Violence and Confronting Religious Judgmentalism, published by Wipf & Stock.

Part 1: A Cultural History of Hospitality

Let me begin with the obvious: hatred, fear, and abuse of the culturally different are not what Jesus taught. It's not what Jewish tradition before Jesus taught. It's not what "pagan" classical tradition believed. Those of us fending off despair about where America is headed under Donald Trump need to know that the positions and beliefs we struggle to defend have this rich, deep cultural history in the West.

And so, first and foremost, those of us advocating for diversity and for decent human compassion for refugees are not advocating anything new. We are not trying to overturn some monolithic cultural norm of radically homogenous, essentially xenophobic human communities turning their collective backs on everyone else. We are defending moral norms that transcend specific religious identities and allegiances, moral norms that go back thousands of years

Here's the deal. How we deal with "foreigners" in our midst is an ancient moral issue. The cultural "purity" celebrated by ethno-nationalists does not in fact have any basis in human culture: "others" have always lived among "us" as a result of trade, diplomacy, employment, intermarriage, and migration (whether coerced, freely chosen, or compelled by circumstances). Human communities have always been mosaics—more or less diverse mosaics, granted, but mosaics nonetheless. And so, we inherent a long cultural conversation about our moral obligations to the culturally "other" dwelling in our midst.

The conversation begins with how we name the people involved. Are they "illegal aliens"—denizens of Mars, perhaps? As Irish philosopher and literary critic Richard Kearney eloquently explains in Anatheism: Returning to God after God, the words "hostile" and "hospitality" share a word-root, a root meaning "stranger" or "foreigner." Faced with something or someone that is foreign to us—someone or something that is essentially different from our prior experience—we have to decide how to react. We can reject (hostility) or welcome (hospitality).

Myth, folklore, sacred texts, and secular literature are all replete with tales of encounters with strangers. Hospitality to strangers was just about the only moral obligation to other people that the ancient Greek gods cared about one way or another. Folklore abounds with strangers offering unexpected gifts and disconcerting wisdom. Paul's epistle to Hebrews echoes an ancient cultural commonplace: "Be not forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares."

Set that up against the Trump administration policy of kidnapping children and using them as hostages in the hopes that such devastating cruelty to children will deter further migration by desperate families. It has recently become public that the Trump administration has thousands more children lost in its maze of prison camps than had been previously reported. "Angels unaware" indeed.

Ancient Jewish tradition took an extraordinarily strong position on the hostile/ hospitable issue. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, emeritus Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, explains in The Dignity of Difference that Jewish scripture only once demands that we love our neighbor as ourselves (Leviticus 19:18), but thirty-six times it commands kindness to the stranger. The Jews are to protect and care for immigrants because their ancestors were immigrants in Egypt—and badly treated as a result. (Most Americans might feel similarly obligated to welcome immigrants because we too are descended from immigrants.) In Jewish thought, Sacks explains, the primary spiritual challenge is not to develop a private relationship with God but rather to come to see God within those who are strangers to us, within foreigners and those who are different in any regard. Kindness to friends-and-family is not morally sufficient, Jewish sages insist. We are called to care for those outside the intimate circle of kith and kin.

The historical Jesus of Nazareth took this familiar "care for the stranger" demand and raised it a step, demanding that his followers love their enemies.

That command, which is central to his originality as a religious thinker, needs a little context. Christians scriptures were written in Greek, and the Greek word used for "love" in these passages did not command the warm-fuzzy affection we feel for friends and family. Greek has separate words for naming the feelings morally appropriate to various categories of relationships, a set of distinctions that disappear when quite different Greek concepts are all translated into the single catch-all term "love." In most contexts, feeling warm personal affection for our enemies would be morally obscene. That's not what Jesus was commanding.

What Jesus did require was this: we must always respect the humanity of our enemies. We must always remain within the moral limits imposed upon our behavior by the fact that our enemies are fellow human beings and cherished members of somebody else's family. We are not to demonize our enemies. We are not to dehumanize our enemies. We are not to resort to violence as a way of forcing others to obey us: killing other people—or causing irreparable psychological harm to their children—is never a "policy option." Nor is the pre-emptive "war of choice," much less the pre-emptive, first-strike use of nuclear weapons. Nor are we to claim it is morally legitimate for us to do to them what they have done to us or to others with whom we are allied: atrocities do not legitimate atrocities in revenge. We are always to remember that every person everywhere is a child of God and bearer of God's sacred light.

God smites no one, Jesus insisted. And so we cannot claim religious justification for smiting one another. Quite the contrary, in fact: thou shalt not kill has been commanded from the very beginning.

This moral heritage does not by itself constitute policy solutions to the problems we face: climate change, affordable housing, income disparity, healthcare costs, etc. But it does offer a set of standards by which any policy—and any politician—might be evaluated.

Part Two: The Roots of Christian Xenophobia

In violation of rudimentary Greek, Roman, Jewish, and Christian moral norms, Trump abuses other people as incessantly and compulsively as he lies. He appeals to parallel vices in his base—racism and xenophobia—in order to sustain their support amidst the threats posed by a Democratic Congress, the Mueller investigation, and growing public outrage over his border policies. If we want to stop him, we must first understand why he has succeeded as he has among white Christians whose religion should have precluded their support.

The prominence of reactionary, harshly judgmental Christians within Trump's base is theologically complex but logically quite simple. They flatly reject classical biblical teachings calling for hospitality toward outsiders and refraining from violence against enemies. They reject classic biblical teachings that all people carry the image of God, and so we have inescapable moral obligations toward all people. As a result, they reject contemporary secular doctrines, derived from these ancient biblical teachings, that all people possess human rights that can neither be surrendered nor taken away. (Note, perhaps, that there is no basis in Greek or Roman philosophy for this radical claim about essential human equality.)

Trump's evangelical supporters don't buy universal human rights because in the 1500s Martin Luther and John Calvin repudiated its theological foundation: for Luther and Calvin, the "image of God" in us was destroyed by Adam and Eve. Only "the Saved" functionally regain the inward "image of God." The Damned are not, in this regard, fully human. The Damned must be controlled—as coercively as necessary—by the community of the Saved. That's why Christian radicals think it's appropriate for them to impose their religious practices on the rest of us, for instance by denying insurance coverage for birth control or refusing civil rights and public accommodations to gay couples.

Anxiety and hostility toward "outsiders" are hard-wired into these beliefs: there's no way for any of us to prove we count among the Saved. Fervent piety, scrupulously correct doctrinal allegiance, and upstanding moral virtue are all necessary for Salvation, but they are never sufficient. Even the best and holiest among us fail to earn the approval of Calvin's remote and vindictive deity. Calvin's God condemns everyone to his eternal torture. But He selects a few—the tiniest slice of humanity—to be Saved. Even they are Saved for no humanly discernable reason: as far as we can see, God's choice is entirely capricious.

As a result, our ultimate fate is not in our own hands. No matter how hard we try, we cannot earn God's approval. We are helpless in the face of his eternal violence—a state of affairs that easily elicits a primal rage. Such rage need not be conscious to influence our behavior—especially our behavior in groups.

The only hope believers can have is what came to be called "inner assurance" of their status in God's eyes: sheer personal confidence that they are Saved. But the flip side of "inward assurance" is chronic anxiety and then increasingly rigid commitment to the rigid demands of doctrinal orthodoxy, religious observance, and proper behavior. Needless to say, such anxious rigidity is easily transformed into remarkable hostility toward outsiders—who are, by definition, the Damned.

Calvin and Luther didn't buy the universality of an essentially sacred human moral dignity because in the 800s the emperor Charlemagne didn't buy it. And why not? Because Charlemagne needed theological cover for his savage campaigns against the Saxons, a non-Christian Germanic tribe.

Charlemagne got what he wanted by using his political power to impose liturgical changes. These changes emphasized both the savage violence of God and God's implacable hatred for the Damned.

Here's how that worked. The church altar had evolved from a literal to a symbolic pot-luck dinner table celebrating God's hospitality and our hospitality in obedience to God: all are welcome and none leave hungry. Under Charlemagne, the altar became a memorial to God's implacable hostility. It was symbolically transformed from dinner table to butcher block, a locus for ritual remembrance of the death of Jesus. Jesus' brutal murder was radically re-defined as a human sacrifice desired by God to assuage God's wrath and mollify God's offended honor. This human sacrifice was necessary to enable God to exempt a very few people from his eternal torture in the afterlife. The eternal violence of God thus provides a moral example of how to treat enemies—an example that Charlemagne pursued against the Saxons.

This fraught division of humanity into Saved and Damned in effect sacralizes the militarism, racism, and xenophobia that Trump advocates: God himself hates and will someday torment eternally all of "them," whomever the targeted population might be at a given moment. Scholars have delineated how Charlemagne's liturgical changes, combined with belief in the pathological violence of a savage deity, built a conceptual structure that provided pseudo-religious justification for crusades, inquisitions, colonialism, and the African slave trade.

This cultural history helps to explain the red-state paranoia and rage that Trump has exploited so successfully. Here's how his electoral map developed: in the 18th and 19th centuries, repeated waves of "Great Awakenings" spread this corrupted version of Christianity all across the rural American South. The Great Awakenings featured religious-revival meetings intended to bring unbelievers to Christ by spreading the fear of Damnation. The revivals also sought to rouse up in the faithful both the rigor and the fervor of America's first Puritans.

In Southern Cross: The Beginnings of the Bible Belt, historian Christine Leigh Heyrman recounts the sweepingly negative social consequences of the acute anxiety these revivals provoked. As she explains, "Many southern whites, both humble and great, believed that evangelicals, by this unsparing emphasis on mankind's sinfulness, hell's torments, and Satan's wiles, estranged men and women from the strong and decent parts of their personalities and plunged them into fathomless inner darkness. From that fall there could be no easy recovery, for . . . self-alienation snuffed out social identity and ruptured communal bonds. All that leavened the isolation of such anguished souls was the company of demons 'black as coal' who abided within and sometimes walked the earth." Some of these men and women committed suicide. Others rejected members of their own families who refused to "come to Jesus." The social fabric of rural communities was devastated by radical religious partisanship.

Therein lies the cultural matrix that Donald Trump has exploited: he offers a parody of Salvation. He hasn't a clue about this cultural backstory of the Saved and the Damned and the violence of Charlemagne's parody of God. But he clearly recognizes and manipulates the hardwired insecurity and defensiveness that the Saved/ Damned dichotomy has for centuries now elicited within white-evangelical circles. In fact, he shares that insecurity and defensiveness himself: his division of the world into Winners and Losers is a direct secular descendent of Calvin's claim that prosperity and social status are evidence of God's favor and thus an indirect marker of Salvation. (Being rich doesn't prove you are Saved, but being poor certainly suggests you are Damned.)

Supporting Trump supposedly confers secure membership in the community of Winners; when he promises to attack Losers with all the force that the federal government can muster, he offers an outlet for the rage felt by anyone who feels both socially and economically "inferior."

That's a uniquely American-Christian-fundamentalist form of fascism. It's also a batshit crazy inversion of everything Jesus taught. But through the Puritans, this inversion is powerfully encoded both theologically and culturally within American discourse. As I explained years ago in Selling Ourselves Short, in America, if you are not rich it's your own fault. You are a sinner. You're Damned. And if you are a desperate refugee, you are undoubtedly Damned.

Add to this toxic heritage the following psychological pressures: the attacks of 9/11; our failed wars in Afghanistan and Iraq; the rise of random mass-murders by alienated white American males; and the financial collapse of 2008. Anxiety this awful will always seek an outlet, most commonly in rage. In sum, the election of someone like Trump looks almost inevitable. We may be lucky, historically speaking, that he happens to be such an erratic buffoon. Ted Cruz or Paul Ryan might have posed a far greater danger because they understands far better than Trump does how to manipulate white-evangelical religious anxiety.

The liberal-progressive Christian Left is the largest group out here that fully understands the theologically complex matrix Trump has exploited, a matrix that remains available to his successors. Progressive Christians have a rich conceptual heritage and ample rhetorical resources for reclaiming the proper functioning of American moral values and civic ideals. We understand how to persuade Trump supporters to re-align with what Jesus actually taught: address their hard-wired religious insecurity with what Jesus actually said about God. Offer them a secure moral identity as Americans. Insist upon American patriotic ideals transparently derived from what Jesus said—and insist that government in fact live up to those ideals.

Many evangelicals—many Trump supporters—are good people who have been lied to and slickly manipulated ever since the first well-funded "prayer breakfasts" to convince local clergy that the New Deal was "godless Communism." A decade later, Republicans sought to block progressive economic policies by allying themselves with white-supremacist Southerners opposed to civil rights and integration. This alliance is on a par with Charlemagne's corruption of the liturgy. Christians on the Left understand all of this. We have been fighting it for generations. And for generations we have watched the Democratic party establishment flounder around, tone-deaf and clueless on religion, flatly unable to counter this corrupt alliance among neo-con militarists, radical libertarians, and Southern evangelical clergy.

Christian progressives know how to tell a resonant new story about American identity. And that's what we need. Here's what that might look like, and why it might work.

Part Three: Defeating Christian Fundamentalist Fascism

Trump might be toppled from his base as quickly as he rose, because white-evangelical metaphysical anxiety is inherently unstable. God is inscrutable. Trump is clearly a "notorious sinner." Scripture is replete with condemnations of politicians like him, just as it is replete with demands that the faithful care for the poor, the outcast, the hungry, and workers deprived of just wages. None of that squares with the radical libertarian crony-capitalism of elites like the Koch network, just as none of it squares with the refusal to address climate change or stop corporate damage to the natural environment.

Furthermore, white-evangelical churches are facing a catastrophic exodus of members, especially among those younger than fifty. Large and growing organizations on the evangelical Left are actively courting these white-evangelical dissidents, providing vital communities for those who insist upon the social-justice agenda of the classic biblical prophetic tradition. For generations now, the Catholic Left and the mainline Protestant Left have exerted similar pressure upon their denominations, all of which face an equally dire exodus of good people disgusted by what "Christianity" has come to stand for in this country.

In short, reactionary white Christians are not the dangerous monolith that secular liberals imagine, just as the immigrant caravans are not the looming threat imagined by Fox News. Reactionary and fundamentalist Christianity is on the brink of collapse. Their political alliance with radical neo-cons and libertarian oligarchs may shift—it may have to shift—if their congregations are going to survive demographically.

And so red-state Christians may to respond to political messages that resonate to the moral values, the concepts, and the poetry of the authentic Western moral tradition I sketched at the outset. They need to come to Jesus, so to speak—to what the man actually taught, not to what this corrupt merger of church-and-oligarchy has turned Christianity into. (This alliance has, if nothing else, proved devastating for them economically, a fact well-documented by Thomas Frank in What's the Matter with Kansas.)

The new generation of unapologetically progressive Democrats have an extraordinary opportunity here to rise above that secular-liberal hostility to all religion. They recognize that not all Christians are fundamentalists, and not all of Christian tradition is pernicious. This new generation seems to care more about what people do—how we act, what issues we support—than about the conceptual origins of our motives. By that measure, the Christian Left are worthy allies. Authentic cultural pluralism makes space for Christians like me and the potent cultural resources we bring with us.

That bodes well. To reweave the national fabric, we need a new story about America's founding ideals, including its vision of universal human rights and government that serves the common good not the one percent. We need to tell a new story about who we are as Americans, a tale that creates and affirms a secure communal moral identity. We need—we have always had—an alternative to the radical consumerist individualism of free-market capitalism, with all of the besieged, anxious loneliness and alienation that consumerism entails. Younger Americans in particular increasingly question the dictum I Am What I Own. They are comfortable with the claim that there's more to life than earning the most money possible—the classic secular version of Calvinist Salvation.

Here's an example of what that might sound like: There is more to being an American than being a Winner in Trump's sense of that word. To be an American is to believe that there is moral dignity in offering compassion and respect to all people, period. There is moral dignity in refusing to exploit or abuse others. There is moral dignity in being good neighbors and responsible citizens who follow the rules and do their part in maintaining the common good (that includes paying a fair share of taxes). There is moral dignity in personal integrity, honest collaboration, hard work, and the refusal to boast.

In behaving with dignity, we affirm the dignity of others. That's the deal. There is no other. If you want to feel respected and valued, you have to offer respect and honor to others. If you want a life that has meaning, you have to see meaning in the lives of everyone around you—no matter what their ethnicity or income or citizenship.

"American" is a standard of behavior towards others. This needs to be said. It needs to be said repeatedly and forcefully. "American" is not a birthright ethnicity like "French" or "Chinese." "American" is moral ideal—a moral ideal richly rooted in Western moral teachings about hospitality and respect for others. America is a nation committed to the belief that all of us are equal and so all of us are equally obligated to one another's well-being.

America has failed repeatedly in the past to live up to its own ideals. We all know that. That doesn't for a moment change what our beliefs are. If we stop celebrating these moral norms, if we stop teaching these beliefs, if we stop demanding them of our elected officials, then America has ceased to be America. We're just a polyglot collection of people who are profoundly suspicious of one another, savagely competing to control the wealth of our land. That's why so many people joke about moving to Canada: it is reasonable to want to belong to a civilized nation.

We can't defeat Trump unless we have something solid to offer in his place. Without a vision, scripture warns, the people perish. If we can work together to reclaim America's vision, we may in fact survive Trump's presidency