For Fidelity discussion leader's guide

Discussion Leader's Guide

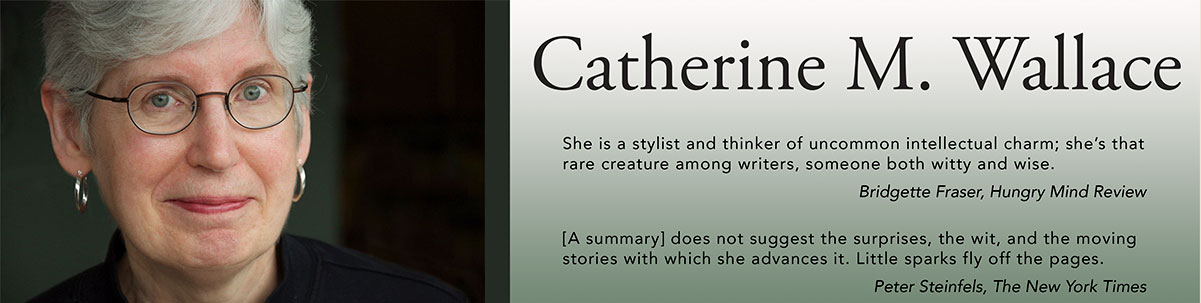

For Fidelity, by Catherine M. Wallace

For Fidelity, by Catherine M. Wallace

Part One. Miscellaneous Management Issues

Whom to Invite and How?

Unless you are bringing For Fidelity into a pre-established book group or fellowship group, the first question will be announcements, advertising, and so forth. I'd like to offer some advice: target the program to parents--parents of toddlers and parents of teens; parents of straight kids, gay kids, grandkids, grown kids; and parents-by-election, those magical folks who are deeply blessed with the gift of nurture even though they don't have offspring of their own. I've lectured to standing-room-only crowds, and I have faced empty halls: the difference is how the program was described. The discussion guide begins with a description of the book that you can use in advertising your own program: to reach it, please click here.

Some people argue that "everyone needs to know" the argument that I make. I am honored by that thought. But it's not persuasive enough to get folks in the door. Wording the announcement properly is crucial because most people have a very limited tolerance for publicly discussing their own sexual behavior or for listening to anyone else describe theirs. If they think that's what might happen, they won't come--and I don't blame them. Furthermore, people who are already committed to sexual fidelity are very unlikely to take time from their busy lives to "come learn about it." But many people are concerned that marriages are proving less and less stable with each succeeding generation, and many people are willing to talk about how to countermand the pop-culture pressures on teenagers and young adults. All of us know about AIDS. Concern for the young offers a much safer, easier angle on the topic of sexuality, and it's a perfectly legitimate public concern in its own right. Because concern for the young is both legitimate and not a threat to our own privacy, a program aimed at parents will easily attract all sorts of folks who are not now actively parenting: educators, counselors, 20- and 30-something folks--married or single--who hope someday to become parents, and miscellaneous lively thinkers of all kinds.

Other folks argue that I engage a much wider and richer range of issues than simply what to say to kids. Again: that's true, and I'm pleased when folks see that; but the appeal to parents is quite dramatically the most effective approach to presenting a program. After all, For Fidelity is not one of those silly patronizing how-to books giving parents set speeches they are supposed to make. If For Fidelity is how-to at all, it is how to think about these issues so that when the moments arise--with our kids or our colleagues, our neighbors or our nephews--then we can speak simply and confidently and from the depths of our own hearts about the meaning of sexual fidelity in our own lives. I feel quite strongly that "what to say to kids" does not underestimate the scope and intellectual substance of my work. Eighty-five percent of adults become parents at some point, and parents need the best thinking that anyone can muster: we have enormous cultural and moral responsibilities. Furthermore, children and youth are eager for and deeply influenced by their friendships with non-parent non-teacher adults. In most traditional societies, the adolescent's ritual transit from childhood to adulthood happens in the company of same-sex adults: it is not the task of the biological parents alone. The modern child's spiritual formation with regard to mature interpersonal ethics is just as inevitably situated within a community of caring adults who understand their responsibility as models of honest friendship and personal integrity. If we do not accept that responsibility, children--everyone's children--are prey to the models offered by movies and television.

What I'm arguing here is painfully-gained marketing advice, but there's more to it that that. There's a theological dimension as well. As living members of the Risen Christ, we are all responsible for one another, and that includes one another's children. "Those responsible for the next generation" excludes no one unless we suppose that children are a form of private property. But in Christian tradition, children are not private property. Every time we baptize a baby we accept specific responsibility for the moral and spiritual development of the next generation. We all need to understand how much we contribute to children's sexual development whenever we set good examples of personal honesty, ordinary responsibility, and loyal friendship. In all probability, any church is doing plenty of the right things already, but we need to see that about ourselves so that we can do these things even more deliberately and more consistently. We also need to know how to use these good examples both in the spiritual formation of children and in our own spiritual journeys. I discuss the tremendous importance of community on pages 86-94: none of us bear these responsibilities or undertake these journeys alone.

Submerged Theological Foundations

Let me begin by pointing out a couple of useful facts. First, I tell a lot of stories: my rule-of-thumb was not to write more than three paragraphs without stopping to tell a story. Second, underneath the storytelling is a very straightforward three-point outline.

A: We have an immediate sexual need for fidelity (Chapter 2).

B: We have a complex psychological need for fidelity (Chapter 3).

C: We have an ultimate spiritual need for fidelity (Chapter 4).

B: We have a complex psychological need for fidelity (Chapter 3).

C: We have an ultimate spiritual need for fidelity (Chapter 4).

The last section of each chapter looks at the question, "But how do we explain this to kids?" My answer is always--one way or another--that we teach our children through the ordinary anecdotes and simple conversation of family life. The last chapter (Chapter 5) pulls together those scattered observations about the role of storytelling within the spiritual formation of families and within the spiritual journey in general. A skilled discussion facilitator can get a group through an over-view of those three points in a single session if that's the program slot that is available.

On the other hand, there is a fair amount of theology submerged underneath this three-point outline. This theology is submerged because I think that a good story persuades more people and explains an idea more vividly than abstract systematics will. But it's there, and I have been asked to do a quick pencil sketch of how it works. I am pleased to do so for those who are interested; everyone else should feel free to skip ahead to the next section, "Deciding Which Questions to Use."

Chapter 2 looks critically at the cultural traditions regarding sexuality, always remembering that the Incarnation shapes or ought to shape Christian attitudes toward bodily experience. I explain the sexual need For Fidelity right at the beginning, segue through some stories describing attitudes toward the body, and then spend most of the chapter describing and evaluating our historical heritage. Much of the work of Christian intellectuals and theologians, it seems to me, is the ongoing, endless task of untangling the truth about God and the truth about us from the complicated webs of popular culture whether of the ancient world or of our own. My principal goal in this chapter is to illuminate contemporary "marketplace" metaphors for sex and for marriage. These pervasive metaphors are very dangerous, because they reconcile conflicting strands in our religious and cultural heritage--in all the wrong ways. My arguments about sexual fidelity attempt to synthesize that heritage in much wiser and healthier ways.

Chapter 3 is all about the psychology of intimacy, which I sketch first abstractly and then through all the little stories about my friends' marriages. Behind the stories or within the stories, however, is a sacramental theology of matrimony. As a believer, I am convinced that intelligent, rational, humane study of our own experience leads us inevitably to what the Rev. L. William Countryman calls "the border of the Holy." The mostly-secular language of For Fidelity can only suggest here and there that enormous religious issues lie just ahead, but attentive readers will quickly recognize where my argument is going. In sustained, committed, sexually faithful relationships, regardless of sexual orientation, we are forced by the suffering of life and by the inevitability of psychological change to endeavor to love one another as Christ loves us. Viewed up close, as stories bring us up close, we can see how incredibly difficult this is. That's part of the reason why many Christian traditions regard marriage as a sacrament: this takes grace. Lots of grace. We do it, when and if we can do it at all, with God's help. Perhaps the marriage vows should be changed from "I do" to "I will with God's help," which is what we promise at baptism. Because this is a general-audience book, I could not use the rich and complicated conceptual vocabulary of grace and sacrament. But you will, I hope, recognize over and over again that sustained intimacy as I describe it depends upon God's grace. In all my little anecdotes and stories, I am trying to turn contemporary anxiety about "the divorce culture" and troubled marriages into a portrait of just how powerful sacraments can be and just how deeply we need them--and just how vividly real they are in our lives.

In a variety of secular settings across the country I have encountered a tremendous yearning for some confident, indeed prophetic claim that with God's help we can make and keep solid commitments to our partners, to our own and others' children, and to each other in community. Our culture, here and now, is desperate for coherent witness to the value and the possibility of sexual fidelity. I am increasingly convinced that many people, many young people in particular, struggle enormously with the question whether or not sustained, sexually faithful relationships are humanly possible for anything more than a very few years. We must support one another--regardless of orientation--in the effort to make the commitments that witness to the power of God's sustaining grace in our lives.

What I say about committed relationships between gay or lesbian people is scattered here and there, but you can find every reference in the index under "homosexuality." The most important passage is in Chapter 2, pp. 49-52: I believe that sexual fidelity is moral norm binding upon all of us, regardless of sexual orientation; and I believe that the churches should support and encourage sexual fidelity among all people, even if these permanent and morally-grounded commitments are made to partners of the same sex.

Chapter 4 is Scripture. Only believers, I suspect, will realize what I'm doing in the opening paragraphs of this chapter. This is what I'm up to: What happens if you answer the question "Is there or is there not God?" in the affirmative? Our need For Fidelity becomes also a commandment to be faithful. Furthermore, the command of fidelity understood in this way reflects not the repressive social control of sexual drives but rather a complex and very demanding recognition of what it means to be called to be human. More powerfully yet, our need For Fidelity with one another reflects and is reflected by our need for faith in the Risen Christ, who assures us that life will continually arise from all of our suffering and all of our uncertainty and all the gritty ridiculous glorious inexplicability of sustained sexual fidelity. Over and over, then, I'm reading these Biblical texts to show how the effort to love our partners as ourselves reflects and is reflected by the effort to love God with our whole hearts. In short, we are to love one another and to love God in the very same way: whole-heartedly.

Let me repeat: Please don't feel that you have to push the trajectory of my argument into more complicated theological issues than whatever comes up naturally from the questions in the discussion guide. Trust your own judgment and, when in doubt, encourage people to swap stories rather than to argue abstractions. The real life of faith has always depended upon storytelling; the book as it stands is a whole and complete thing--even its footnotes are entirely optional.

Selecting Which Questions To Use

One session. If you are going to use the discussion guide for a single session, I'd suggest selecting from questions 6, 8, 10, and 12. But please defer to whatever folks want to talk about the most. Trust grace, in short. And trust your knowledge of your own community.

Two sessions. If you plan to discuss For Fidelity in two sessions, focus the first on my argument about why casual sex is wrong (selecting from questions 1-9), and the second on some combination of how marriages do actually survive and how we can help children to develop the necessary virtues (selecting from questions 10-14). Again: these are only suggestions.

Four sessions. If you can manage four sessions, combine Chapter 1 with Chapter 2 in a first session, do Chapter 3 in the second session, Chapter 4 in the third session, and combine Chapter 4 with Chapter 5 in a last session.

Six sessions. If you want to do six sessions, combine the first two chapters into the first session, but then do one chapter per session thereafter. This leaves you with a last session for which there is no new reading: when everyone has a chance to catch up, the discussion is often particularly rich. There are two major issues to consider here. I suggest that you begin the last session by asking people to identify in their own words what seems most important about the argument I present in For Fidelity. I would gradually steer the discussion toward a broader consideration of two distinct but closely related issues. First, identify what the parish is already doing that parents can use to help their children recognize Christian norms for interpersonal ethics. Is there anything more you can do? Secondly, identify what the parish is already doing to provide active, on-going support to sexually faithful, life-long committed relationships, regardless of sexual orientation. Is there anything more you can do?

Let me explain how these two issues are interdependent. If the Great Commandment has a bearing on our sexual lives, then it must do so universally, without regard for orientation, youth, age, financial situations, or our claims about our own maturity. Furthermore, our children are watching: young adults are quick to gauge the seriousness of our ideals by the consistency of our behavior. Any exemptions we offer to anyone they will claim for themselves. If it is acceptable for single adults in their forties or their eighties to have sex outside of committed relationships, it will be very difficult to persuade young people that we have a solid moral basis for claiming that they should not do so. I grant that there are many very complicated legal issues because clergy function as representatives of the state for the purposes of marriage. The fact remains that the local church can be and always has been a stubbornly visionary, deeply creative community. We must continue to be so.

Getting and Using the Discussion Guide

The discussion guide questions are posted elsewhere on the Reading Group Guide site: please click here to reach it. In the manner of all such publishers' guides, it endeavors to sustain a thorough and systematic discussion of the book's principal argument. Some discussion leaders prefer a much less structured approach, asking open-ended questions of the form "Let's look at page XYZ, at what she says about thus-and-such. What do you make of this passage? What do you think about thus-and-such?" That way everyone is on the same page, literally; and the group is free to find its own balance between the book and the issues as such. This approach demands somewhat more experience or skill from the discussion leader, but it can be very effective. In the chapter-by-chapter guide below, I identify appropriate page numbers for the major topics addressed in each set of questions; these referents are useful no matter where you find yourself on the structured-unstructured continuum of discussion leaders. The relevant passage usually goes to the end of the paragraph; sometimes it's longer but ordinarily you will see that for yourself. Once in a while I will tell you how far the "answer" goes.

Less-experienced discussion leaders need to keep in mind that books groups and parish groups are ongoing communities of people who care about one another, who respect one another's ideas, and who want to hear one another's opinions and stories. The group itself is at least as important as the book, which is a catalyst around which the group re-constitutes itself and reaffirms itself as an ongoing Christian community. The book is an invited guest, a new conversation partner. You have invited me, the author, at one remove. If I were actually present, I would certainly not dominate the discussion in some overbearing way. Don't let the discussion guide behave rudely either, so to speak. Where the questions strike you as genuinely interesting, use them. Otherwise please don't.

The discussion guide was originally written by me for my publisher, and so it offers an entirely secular, general-audience set of questions. Faith communities share an enormously rich and complex framework within which to address such issues. Once in a while the study guide includes questions hinting at this framework: I'm sure you will recognize these on your own and make use of them as appropriate. At times the study guide also invites people to tell stories of their own. I would encourage you to encourage that.

Following some of the questions I offer a few additional comments explicating submerged theological and religious issues--building upon section B, above. Use this material or not, as you prefer. If you want further help in trying to foresee what a fully-grounded theological argument against casual sex might look like, I recommend the discussion of "Thou shalt not commit adultery" in chapter six of Stanley M. Hauerwas and William H. Willimon, The Truth About God: The Ten Commandments in Christian Life (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1999). It's classic Hauerwas-and-Willimon: short (ten pages), down-to-earth, witty, pointed, accessible, and yet tremendously sophisticated account of how the commandment against adultery can be understood as outlawing casual sex. Casual sex between two single people does not necessarily or obviously constitute adultery, after all. In ancient times, nonmarital sex was forbidden under "Thou shalt not steal." Because women were regarded as property, unmarried sex was theft by one man of what properly belonged to another (the father or the husband of the woman). If women are not property, the commandment against theft doesn't work, at least not at the literal level.

Managing the Discussion

Sociologists insist that every ongoing social group has implicit "rules" governing everyone's behavior. When you have a new group, or an established group under new or particular pressure, it is very wise to begin by agreeing upon ground rules. That's not quite as simple as it sounds: there are large but perfectly legitimate differences in how people go about expressing themselves. Although once in a while discussions are disrupted by a genuine bully, more often those who argue or who disagree are honestly trying to clarify--not to antagonize. The challenge is to manage differences in style so that no one feels silenced by someone else's direct questions or by the good-hearted bluster of extreme extroverts. When someone does express an opinion in an absolutist way that I think is intimidating others in the group, I find that it helps to respond something like this, "OK, so Miranda dislikes watermelons. That's her feeling on this topic. What other points of view do we have here?" If you are an experienced leader, you already have your own ways of handling the usual mix of personalities in your own community. If you are new to the game, here are a couple of ground rules you might propose.

1. Everyone has the right to remain silent. Feel free to declare yourself a "designated listener" if someone asks you a question you don't want to answer or tries to corner you into having an opinion when you don't want to say anything.

2. Everyone has the right to be heard. We don't have to agree with one another, but we do have to listen honestly and openly. We need to hear the full range of opinions.

3. Everyone has the right to hear everyone else. If someone is speaking too softly, ask them to speak up; if you think someone is being silenced, assert your own right to hear what they want to say.

I have some specific management suggestions to make concerning the discussion of question 8 for Chapter 3: these can be found with that question, below.

Part Two. A Guide to the Guide: Leader's Notes

CHAPTER ONE

1. Chapter One (pp. 3-24) provides an overview of the quandaries besetting any consideration of sexual behavior. When should parents start to talk with their children about sexuality? Is "just say no" an effective practical response to adolescent sexuality? Is it morally and intellectually sufficient? Can--or should--parents assert absolute authority over their children's sexual behavior? Has religious faith or spiritual belief played a role in your thinking about these issues? How or why or why not?

Relevant passages: "just say no": p. 6, beginning "No matter what." Sex and sin: p. 4, "Sex education, 1990's style," and p. 8, "Furthermore, both Protestant"

2. Do parents today face questions about sexuality in a sharply different cultural climate than parents of earlier generations? Do you think that many parents have different, more skeptical or more critical attitudes towards "the sexual revolution" than they had as teens and young adults themselves? Why do you think these attitudes have changed? What should parents do if they feel that they make some mistakes in their own sexual choices over the years? Should they talk honestly to their teenagers about what experience has taught them?

Relevant passages: what time has taught us: p. 7, "Most powerfully of all."

3. What is the difference between sexual fidelity and mere sexual exclusivity? Is there "something more" to marital fidelity than rules about who sleeps or does not sleep with whom? As you look at your own experience and at the lives around you, to what extent to successful marriages look like a set of carefully negotiated rights and obligations, and to what extent do they resemble a creative process?

Relevant passages: sexual fidelity vs. sexual exclusivity: p. 13, line two down, beginning. "Sexual fidelity is more than."

4. What does it mean that sexual fidelity is intrinsic to marriage? Can people have both a long happy marriage and multiple sexual partners? To what extent is a happy marriage a matter of good luck and to what extent does it depend upon serious, sustained effort by both partners.

Relevant passage: intrinsic: p. 16, "Marriages requires" + next three paragraphs.

Further considerations: What about church teaching? Is fidelity intrinsic to the sacrament of matrimony? Why? Is it just that sexual exclusivity is the traditional expectation, or the means to insure legitimate offspring? Or is there more to it than that? What do you hear in the wording of the usual marriage vows? The Book of Common Prayer, for instance, phrases it this way: "N., will you have this man to be your husband; to live together in the covenant of marriage? Will you love him, comfort him, honor and keep him, in sickness and in health; and, forsaking all others, be faithful to him as long you both shall live?" The man, in turn, is asked exactly the same questions. After readings and a homily, the following vows are exchanged: "In the name of God, I, N., take you, N., to be my wife [or, my husband], to have and to hold from this day forward, for better for worse, for richer for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish, until we are parted by death. This is my solemn vow."

CHAPTER TWO

5. Chapter Two (pp. 25-55) argues that we have an immediate erotic need For Fidelity. What is the difference between "I am a body" and "I have a body" sorts of experiences? Have you ever had experiences of one kind or the other? Do you agree that both claims or both kinds of experiences are true, each in their own ways? What cultural traditions or inherited attitudes and opinions have influenced your thinking in these regards? When has that influence been helpful, and when has it been detrimental?

Relevant passages: "I have a body:" p. 28, line 3 down, "Even at the end" to bottom of page. "I am a body:" p. 31-32 , line 2 up, "Athletes, dancers" to middle of next page. Both true: p. 33, "As we review" to top of next page.

Further considerations: What do Scripture and Christian tradition broadly considered teach about the significance of the physical world or physical, embodied human experience? Does it count? What attitudes toward the body did people pick up from church experience when they were growing up? Don't get stuck on "sex ed" topics only: consider church music, stained glass windows, liturgical pageantry, and all of the famous traditions of Christianity and the arts. What about the sacraments as "I am a body" concepts? What about the Incarnation? It is far easier to get to my "sex is holy" conclusion from within high sacramental religious traditions and from within a deeply serious understanding of the Incarnation because that's where or how my own sensibilities were originally shaped. Sacramental theology surfaces again--or is again submerged--at question #7, below.

Furthermore: I talk about fidelity using terms and concepts drawn from the arts, because I am writing for a broad general audience. But Christianity itself also provides an excellent conceptual framework. Christians understand that spiritual development is a path or a journey, a way or a method, that leads to an ever-deeper capacity for integrity, compassion, and wisdom. Regardless of orientation, sexually faithful, committed relationships demand integrity, compassion, and wisdom: such relationships are a classical form of spiritual discipline.

Finally: when I say that both "having" and "being" a body are paradoxically true, I am trying to transcend logic and definition in ways that philosophy does not allow but religion demands and storytelling accommodates beautifully. See p. 86, "Despite their failures" and Chapter 1, note 1, pp. 147-149.

6. What is the difference between mind-over-body self-control and wholistic integration? Can you have one without the other? Should you have one without the other? Can sexual morality be grounded in psychological integration or whole-heartedness rather than in strict sexual self-control? Why--or why not? Can sexuality morality be grounded both in psychological insights and in religious tradition simultaneously? Why or why not?

Relevant passages: self control: pp. 43-44, "But we do not share" through middle of next page. Integration: p. 35, "All energy is bodily" and pp. 32-33, "In wholistic." One without the other: p. 41, "Gleefully hedonist," and p. 36, "Sexual ethics from," and p. 56, "Sexual desire can" + next paragraph

Further considerations: Psychology vs. religion: As I see it, there is no theoretical conflict or incompatibility between faith and ordinary human intelligence about our own experience. Psychology is (or can be) a dimension of God's on-going self-revelation and presence among us. There is not, in principle, any need for an either/ or choice here. What I'm trying to get at is how sophisticated modern psychology reflects, at least in part, a rediscovery of "whole-hearted" psychology and therefore "whole-hearted" moral norms that are both profoundly Biblical and sharply at odds with severe Enlightenment rationalism, which is both a resurgence of Manichaean psychology and a foundation for modern radical individualism. Check a biblical concordance under "heart" (at least for the RSV) if you want to expand this issue.

7. Are hedonism and repression the opposite of one another? Or do they both depict sex as "just a physical thing"? Do you agree that marketplace concepts like cost-benefit calculations shape a lot of contemporary thinking and talking about sexual relationships? How does "the dating game" or the "singles scene"--especially as represented in movies and on television--manage to combine the worst aspects of hedonism and repression? Do sex-education programs in your community feed into this marketplace individualism? What alternative traditions or communal resources are available?

Relevant Passages: Hedonism: p. 36, the whole page. Repression: pp. 44-45, "Under pressure of time." Marketplace" metaphors: pp. 52-54, "So Freud and Augustine." Sex ed programs: pp. 40-41, "Maybe we fooled our parents." Contraception or non-procreative sex: p. 46-49, "For centuries, then" and p. 69, "Living with somebody."

Further considerations: If time is short or people are uncomfortable talking about historical figures they have not read, you can probably skip Freud and Augustine altogether. Not everyone finds historical background as useful or as interesting as I do: that's okay. My key point here is that hedonism and repression both claim that sex is "just a physical thing" in ways that generate marketplace metaphors for sex and for marriage. That claim wildly contradicts a sacramental view of life, it seems to me; and it is entirely at odds with the Incarnation as an ongoing reality in our lives. The psychology of "just a physical thing" gets looked at critically in the next chapter.

CHAPTER THREE

8. Chapter Three (pp. 56-61) argues that we have a profound psychological need For Fidelity. How is sexual desire different from other physical desires and needs? According to this chapter, what's wrong with casual sex between consenting adults? Do you agree with this conclusion? What's wrong with the idea that sex can be a casual expression of friendly affection with a variety of partners before marriage, and then function successfully as the embodied language of commitment after marriage? Do you agree that sexual intercourse "ought to be the exclusive and embodied language of commitment between two people"? Should these prohibitions and moral norms apply with equal seriousness to same-sex relationships? Why or why not?

Relevant passages: Sexual desire as unique: p. 25-26, "Let me begin," and p. 56, "The answer demands." Why casual sex is wrong: pp. 58-59, "My short answer." Sex as both casual affection and embodied language?: pp. 58-59, "Of course many people." Same sex relationships: pp. 49-52, "Dualist Christianity"

Further considerations: Because I was writing for as wide an audience as possible, I did not use a Christian framework of my argument. But if I have made a convincing argument that casual sex is exploitative and self-denigrating, then it is sinful. It is forbidden on that grounds alone, even though there are other grounds to which one might refer. Hauerwas and Willimon, The Truth About God chapter 6 explain in some detail how the commandment against adultery can also be understood as forbidding casual sex.

Further suggestions about managing the discussion:

Any argument can be refuted: I propose that you evaluate my argument against casual sex as rigorously as possible. Doing so may place people in the rather strange position of appearing to advocate casual promiscuity, so a little extra structure might prove very helpful.

I suggest that you ask the group to brainstorm counter-arguments. Make it very clear that people do not have to agree with a counter-argument in order to suggest it. The goal here is not self-revelation but rather a complete list of every possible refutation that might come from any source at all--including quick-witted college students and movie-watching sixteen year-olds! What we need at this point is a clear portrait of the popular culture pressures and arguments to which all of us, including vulnerable young adolescents, are subject all of the time.

Then go through the list and ask how they imagine I would answer these objections, and whether or not they think my answer is intellectually solid or theologically persuasive or would convince an angry seventeen year old. Once again, people don't have to agree with me to offer the answer they think I would make, nor must they disagree with me to conclude that my answer isn't very strong or it's not persuasive or it wouldn't convince a self-assured twenty-one year old. Asking people "what Catherine Wallace would say" once again offers a opportunity to engage the issues without seeming to require that anyone reveal their own attitudes or practices with regard to sexuality.

Nonetheless, keep in mind that no safeguard works all the time or in every group. Please be as alert as you can be that no one is silenced and no one is put on the spot. (I like having a Designated Watcher to help me spot the silenced or the unhappy, especially when I'm a stranger to the community.) As Christians we are morally accountable to each other, but a book discussion group is the wrong setting in which to criticize one another's lives. The goal here is critical evaluation of an argument in a book. That evaluation has to be thorough and solid if people are going to leave equipped to meet the arguments made by young people who are under remarkable moral pressure from the popular culture. It may also prompt individual examination of conscience, I realize; but if so that will happen afterwards and privately or with the confidential help of a spiritual director, confessor, or good friend.

When you get to the question about same-sex relationships, please remind folks that I distinguish repeatedly between morally-committed relationships and those legally registered with the state as marriages. Discussions can bog down in confusion, because we don't have a familiar one-word label for morally committed relationships that are not legally registered as marriages. And yet, moral status and legal status are two different things: see p. 53-54, "In the world;" p. 61, "Traditionally, that sort;" p. 83, "As I said before;" and p. 86, "Ideally, marriages."

9. How does Wallace define marriage? Is that an adequate definition? What is the difference between seeing marriage as a licensed activity bound by a legal contract and seeing marriage as a sexually embodied friendship bound by a moral commitment? Why do we have licenses and laws pertaining to marriage? Do they help people to understand how marriages work or why they succeed? What is the difference between seeing marriage as a moral commitment and seeing it as happily-ever-after romantic bliss?

Relevant passages: Marriage defined: all of pp. 61-62, and pp. 65-66, "To an individualist," and pp. 77-78, "Intimacy creates."

10. How does the security of a serious and permanent commitment to the relationship facilitate the development of psychological intimacy? How does the experience of intimacy influence a person's ongoing adult development? In that regard, what is the connection between vulnerability and compassion? Take another look at the specific behaviors or virtues underlying successful marriages (pp. 69-85; see also the table of contents, p. x). Are such virtues appropriate only within marriage? Are these virtues familiar to you from religious teaching or other sources of wisdom about interpersonal morality? Do they seem characteristic of the happiest intimate friendships and marriages that you know? Why might it be easier to attain these moral ideals of personal responsibility within an intimate and committed relationship than with other people in general? What role might a community play in supporting or in discouraging these virtuous ideals?

Relevant passages: Commitment and intimacy: pp. 66-68, "Real intimacy." Intimacy and adult development: p. 66, line 3 up, "Just as new life." Vulnerability and compassion: pp. 68-69, whole section. Moral ideals: p. 73, "Intimacy also demands" and p. 75, "It remains crucial." Community and virtue: pp. 86-90.

CHAPTER FOUR

11. Chapter Four (pp. 99-132) argues that we have an ultimate spiritual need For Fidelity. What are the three layers of meaning shaping the concept of "blessing" in the Bible? How does the concept of blessing undercut our tendency to claim personal credit for our achievements? Why is claiming that kind of personal credit a hazardous proposition no matter what? Does it make sense to you that it can be a blessing to survive catastrophe and suffering with our humanity intact? Is it, for some people, a blessing to get a divorce--or to survive one? How can the concept "blessing" help marriages to survive bad times without breaking up?

Relevant Passages: The three meanings of blessing: p. 106, "For the Jews," and p. 107, line 3 up, "By easy or obvious." Blessing and taking personal credit: p. 108-109, "Herein lies" to middle of the next page. Blessing and suffering: p. 109-111, "And that point." Blessing and divorce: p. 112.

12. Sarah and Abraham: How is the open-ended, unconditional commitment of fidelity in fact an ambiguous, distinctly hazardous undertaking? Why should we undertake it? Jacob: How does sustaining a committed relationship over a long period become a life-defining or identity-defining struggle? Can we let ourselves be influenced by other people without necessarily betraying our own identity? Mary of Nazareth: How is fidelity--in our marriages, in our lives generally--a confrontation with or a liberation from consumerist self-absorption and psychological slavery to the rewards and demands of the workplace? Psalm 1: How is fidelity a spiritual discipline or practice rather than a product or a state that we either attain or fail to attain?

Relevant Passages: Sarah & Abraham:, p.115, "The story of." Jacob: pp. 121-122, "Blessing is no passive." Mary: pp. 126-127, "Successful careers." Psalm 1:130-131, line 4 up, "Wisdom traditions variously."

CHAPTER FIVE

13. Chapter Five (pp. 133-146) describes the ways in which we can help children to develop a capacity For Fidelity both in marriage and in all relationships. Why is fidelity important to any real friendship of any kind and at any age? Can you remember times when a friend's kindness or loyalty or support made an important difference in your own life or in the lives of children that you know? Do you think it is likely that someone could attain fidelity in marriage but remain a ruthless, exploitative person in other relationships? What does that suggest about when and how children develop the capacity to sustain faithful, happy marriages?

Relevant Passages: Fidelity and friendship: pp. 133-135, "Even little kids."

14. How do moral, familial, and religious traditions help to sustain and strengthen children when they are under peer pressure? Were such things helpful to you when you were growing up? What's inadequate about letting children think that the difference between right and wrong is an entirely subjective, personal matter grounded in private opinion? How do telling stories and listening to stories help parents to teach their children about the role and importance of the virtues? What stories about moral expectations or moral achievements do you remember hearing as you grew up? How do such stories influence attitudes and behavior?

Relevant Passages: Children and tradition: pp. 138-139, "And here too." Children and story-telling: pp. 139-140, "When we tell a story" and pp. 143-144, "And so it behooves us."